Key Takeaways & Goals:

Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) has a rapid reproductive cycle, with the ability to breed an entire generation every 10 days during the summer. Traditional approaches to managing SWD have involved aggressive spray programs.

UNH researchers are studying cultural integrated pest management (IPM) strategies to prevent SWD populations from establishing and growing. These strategies include using organic-approved sanitizer sprays that remove yeast food odors from the fruit and leaves and investigating the use of weed matting to hinder the SWD reproduction cycle.

The use of a parasitic wasp called Ganaspis brasiliensis is being researched as a potential biological control agent for SWD, however, the distribution of this wasp for commercial use is not yet available.

The timing and severity of SWD outbreaks can vary due to changes in long-term climate patterns and weather variability. Warm, wet conditions can lead to a population explosion of SWD, causing significant infestations in fruit crops.

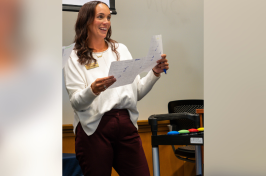

COLSA Student Researchers: Examining Real-World Issues, Finding Innovative Solutions

Catherine Doheny Coverdale earned her Bachelor of Science in Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems—with a focus on food access and community health—before pursuing her Master of Science in Agricultural Sciences at COLSA. She’s worked in the lab of Anna Wallingford since 2020.

"I was influenced to pursue agricultural research after working on a farm that implemented integrated pest management (IPM) practices," said Coverdale. "It was there that I gleaned a deep understanding of the hard work that goes into providing a community with fresh flowers and produce, as well as the importance of sustainable farming practices.”

She added, "IPM research is vital for local food systems. This method of pest management ensures that farmers can achieve profitable yields while minimizing environmental impact. And developing research questions that align with the needs of local farmers fosters a more collaborative and resilient approach to achieving agricultural sustainability."

A New England summer isn’t complete without a slice of juicy blueberry pie and eating a few crisp berries as an afternoon treat. But the spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii), or SWD, a pesky fruit fly native to Southeast Asia that was first identified in the U.S. a little more than a decade ago is wreaking havoc on fruit crops producers—from commercial farms to the backyard garden. New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station scientist Anna Wallingford is seeking new approaches to manage a rapidly growing challenge that already causes hundreds of millions of dollars in crop losses annually to the U.S. and is a yearly threat to more than 41,000 acres of wild and cultivated blueberries across New England.

“SWD impacts everyone who grows fruit and can be found in every region of the state,” said Wallingford, a research assistant professor in the UNH College of Life Sciences and Agriculture. “When it first came on the scene, many fruit growers in the Northeast were left with two choices: adopt aggressive spray programs or bulldoze over their blueberries and fall-bearing raspberries and plant something else.”

Unlike native fruit flies that lay their eggs in rotting fruit and other organic matter, SWD prefer ripe or ripening fruit that’s still on the bush waiting to be picked. Once the eggs hatch, the larvae eat and grow in the fruit, which becomes mushy and falls to the ground. Larvae enter the soil, pupate (transform to their adult stage) and emerge to attack the crop again. During the summer, SWD can breed an entire generation every 10 days, resulting in exponential population growth.

“Over the past 10 years, many folks have learned to live with this pest and adopted several IPM [integrated pest management] strategies to offset many of those sprays,” she added. “The cultural and biocontrol strategies that we’re investigating will contribute to reducing that pressure.”

Investigating Weed Matting & Sanitizer Spray

Cultural strategies or controls are used to prevent pest populations from establishing and growing. Catherine Coverdale ’22, a graduate student in the Agricultural Sciences program and a member of Wallingford’s IPM lab, is currently examining the use of an organic-approved sanitizer spray that removes yeast food odors, which attracts the flies, from the fruit and leaves. She is also investigating whether using fabric covers—primarily intended to prevent weeds in orchards—could also help slow or stop the reproduction cycle of SWDs.

“Blueberries used to be a really low-intensity crop, so growers didn’t have to use a lot of management practices until this fly arrived,” said Coverdale. “Now they’re having to do regular spraying and sanitizing of the fruit, making growing them and other berries much more time intensive.”

By using weed mats below blueberry bushes, infested and fallen fruit lands on the mats and prevents the larvae from being able to reach the soil. This impedes the insect larvae from burrowing into approximately the top 2 centimeters of soil, where they prefer to pupate in a protected, humid environment.

“Summer 2023’s warm wet conditions have already resulted in a population explosion that’s 3-4 weeks earlier than the previous year—so it’s shaping up to be a doozy of a year for SWD infestations.” ~ Anna Wallingford, research assistant professor, COLSA

“The weed mat both reduces weeds and creates a barrier between the SWD larva and the soil environment,” added Coverdale. “It’s also possible that the mats reduce humidity and increase reflective light and temperatures—none of which the larvae prefer—so we’re investigating the light reflectiveness, humidity and temperature of two different mat types as well.”

Ganaspis Brasiliensis as a Cultural Control

Future research in Wallingford’s lab will focus on using Ganaspis brasiliensis—a small parasitic wasp that lays its eggs in the larvae of SWD, specifically those in blueberries—as a biological control. Wallingford and her team are currently growing this parasitic wasp for distribution and release at New Hampshire farms. The Granite State is just one of about 20 states with Ganaspis brasiliensis rearing programs; in other parts of the country, researchers started releasing these wasps in the summer 2022.

Left: A fly trap used to determine the presence of spotted wing drosophila and the start of management practices at the Woodman Horticultural Research Farm. Right: A Ganaspis brasiliensis laying eggs in spotted wing drosophila larva within a blueberry. Photo by Dr. Kent Daane, University of California, Berkeley.

“We’re part of a group of researchers investigating whether or not lab grown Ganaspis brasiliensis are reproducing and establishing in SWD populations after we’ve released them in the field,” said Wallingford. “However, we’re just at the research stage of things, so these biological control agents won’t be available for purchase anytime soon.”

SWD populations remain low in the springtime, meaning that strawberries and some of the earlier maturing blueberries and raspberries often face lower infestation levels. When humidity and temperatures rise and create ideal for SWD reproduction and growth, populations of the invasive pest can grow rapidly. While these conditions are typically seen in July, changes in long-term climate patterns and weather variability could make the timing and severity of SWD outbreak less predictable.

“The hot, dry conditions of summer 2022 kept SWD populations low,” said Wallingford. “However, summer 2023’s warm wet conditions have already resulted in a population explosion that’s 3-4 weeks earlier than the previous year—so it’s shaping up to be a doozy of a year for SWD infestations.”

This material is based on work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch award numbers 1022400 and 7004988) and the state of New Hampshire.

On the UNH Extension website, you'll find additional information on monitoring for SWDs and trapping them.

-

Written By:

Nicholas Gosling '06 | COLSA/NH Agricultural Experiment Station | nicholas.gosling@dos5.net